The Titian Portrait

The Titian Portrait - book excerpt

THE PRIVATE JOURNAL OF QUEEN MARY I, GUILDHALL, LONDON FEBRUARY 1554

It is February 1554 and I prepare to make one of the most important speeches of my life.

It is an icy-cold day with frost-encrusted roads, buildings, carriages, and stone edifices everywhere. The carriage rattles and crunches along slowly, dipping unceremoniously into the potholes and rising again with a shudder and squeal to continue its rocky journey. People are abroad and on the move along the highways, huddled into their smocks and coats, hats and caps pulled down tightly over their heads in attempts, mostly futile, to keep out the cold. Most of them stop their movement and take off their hats and caps, bow towards the carriage and wave to me. I raise one hand repeatedly until it positively aches with lifting continuously, as we progress. I should smile more, and I am aware that I could make the effort and indeed I determine in my mind to do so. The people expect it, and I should accommodate them; I need their support and intend to acquire and keep it.

The Strand is packed with people, all excited, some cheering, others making a strange guttural murmur. They spill out across the road, impeding the progress of our carriage and those following. I am irritated at the number of stops and starts we are obliged to make. The officials herd people and push them back towards the edges of the buildings and we move forward again, the horses spurred on to run a little faster. I lean back against the cushions and take a few deep breaths. As we draw up outside the Guildhall finally, I am losing patience with a journey that appears to have taken far too long but I must keep my irritation in check, or I shall lose focus on why I am here and what I am resolved to do.

Lord Howard and the courtiers escort me through the building and into the Great Hall. The people are crowded into the hall, jostling each other and the murmur of voices, magnified by the sheer numbers of those present, appears to my ears like a subdued roar. Looking out at the mainly ragged, bustling assembly in front of me, I suddenly feel a spasm of panic. Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Salisbury and my Lord Chancellor, is smiling.

“Your chance, Majesty, to rally the troops,” he says, grinning.

“Easier said than done, Stephen,” I tell him with a frown.

“Just seek out one head in the middle of the hall,” he suggests reflectively. “Focus on that one head throughout and it will be just like speaking to a single person, I assure you.”

I raise an eyebrow and give him a sceptical glare.

“No, really, Your Grace, it works, believe me,” he continues, eyes glinting. “Just try it.”

They are all there in front of me, a large and motley assemblage indeed. Farm workers and labourers, carters and coachmen, cobblers and candle-makers, bakers and beggars. Friars and ferrymen. Blacksmiths and butchers. All waiting patiently for me to speak.

Howard asks if I am ready.

“As ready as I ever will be, My Lord,” I tell him. “Let us begin.”

I approach the rostrum and take another deep breath. I nod towards Howard and he bows briefly. I take a deep breath in readiness.

“I am come to you,” I begin, “in mine own person, to tell you that which already you do see and know, that is how traitorously and seditiously a number of Kentish rebels have assembled themselves against both us and you.” The murmur of sound in the hall rises perceptibly for a few seconds and subsides to uneasy silence as they wait upon my next words.

I sense already the collective mood of these good people, that they are with me, their queen, and the silence all around me is only an indication of their shock and dismay. I see on their faces, those closest to me at any wise, the sense of outrage already building.

“Now, loving subjects,” I go on, “what I am you right well know. I am your queen and at my coronation, when I was wedded to the realm and the laws of the same, ye promised your allegiance and obedience unto me.”

Murmurs of assent are now heard in the hall and I remind them that I am the right and true inheritor to the crown of this realm of England and again assert that acts of parliament confirm this.

I tell them, raising my voice slightly, that I do not believe they will not suffer so terrible a traitor as this Wyatt has shown himself to be, to subdue the laws to his evil and give scope to rascally and forlorn persons to make general havoc and spoilation of their goods. I pause briefly to breath in and take measure of the atmosphere in the hall. They are with me to a man; I can sense it – I can almost feel it.

It is time to consolidate my advantage. I must take immediate advantage of the sympathy I feel coming from the people in front of me.

“I cannot tell how naturally a mother loveth her children for I was never the mother of any but certainly a prince may as naturally and earnestly love subjects, as the mother loves her child. Then assure yourselves that I, being sovereign lady and queen, do as earnestly and tenderly love and favour you. And as you heartily and faithfully love me again; I doubt not, but we together shall be able to give these rebels short and speedy overthrow.”

The cheer that erupts from the hall is deafening. Some raise their fists in salute, but all are vocal, whether moving or still. I pause, breathe deeply once again and look over to my right and receive a glance acknowledging the success of the speech from the expression on my Lord Howard’s face and the lingering smile on the face of William Paulet, my Lord Treasurer. Gardiner too is grinning contentedly. I permit myself the very ghost of a smile on this sombre, momentous occasion and raise my hand to request silence. What more to say? I realise I cannot conclude my speech without reference to the stated cause of the uprising and I assure them that I entered into the intended marriage only with the advice of my privy council, the same to whom the king, my father, committed his trust. “And they not only thought it honourable, but expedient, both for the wealth of our realm and of all our loving subjects.”

I assure them heartily that I would not put a wedding and my own lust first but would be prepared, with God’s blessing, to continue as a virgin. “But it might please God that I leave some fruit of my body behind me, to be your governor. I trust you would not only rejoice but also find it great comfort.”

I go on to say that I would enter no marriage that would not be to the benefit of the whole realm and receive the approval of the nobility and commons in the high court of parliament. “If this marriage be not for the singular commodity of the whole realm,” I say with measured, grave tone, “then I will abstain, not only from this marriage but also any other whereof peril may ensue to this most noble realm.”

Cheering breaks out once again, louder this time than before and longer sustained. It was always my intention to finish this speech with a suitable rallying call that had to be exactly right. If my memory or even speech should falter for an instant, I might lose any advantage and support from my subjects that I had gained. I incline my head to give the signal to Howard and he hands me the parchment where the words are written out. I begin slowly.

“Wherefore now, as good and faithful subjects, pluck up your hearts and like true men stand fast with your lawful prince against these rebels, both our enemies and yours, and fear them not; for I assure you I fear them nothing. I will leave you with my Lord Howard and my Lord Treasurer to be your assistants, with my Lord Mayor, for the defence and safeguard of this city from spoil and sacking, which is only the scope of this rebellious company.”

When the uproar of applause, stamping and shouting abates at last and the good people start to move towards the doors, I turn away myself and walk over to my councillors.

“It’s up to you now, William,” I tell my Lord Treasurer.

“That was a magnificent speech, Your Majesty.”

“Yes, very well done indeed,” Bishop Gardiner agrees.

“You think so?” I walk slowly with him, Gardiner and my Lord Treasurer William Paulet into the adjoining chamber where they are preparing to serve refreshments. “Not a little overdone, you might think?”

“Most certainly not,” Howard says soberly, waiting until I am seated before joining me on my right-hand side. So now, I suggest carefully, measuring my words slowly, he would be able, would he not, to raise sufficient numbers of militia to crush these vile rebels?

“I am confident,” he responds swiftly.

“Sufficient numbers, William, sufficient numbers. And we would need several thousand.”

The servants are bringing in roast boar, chicken with cherries, artichokes and large tumblers of sweet French wine. Good, crisp bread, freshly baked, is also provided and I do not stand on ceremony but begin to eat, thereby allowing my councillors to follow suit. The food is good, well roasted and refreshing after my long speech. I eat quite heartily, which is unusual for me but then these are unusual times and there is a rebellion to be suppressed. They add roasted swan a little later and I indulge as it is a delicate meat of which I am particularly fond. Everybody seems to be in jubilant mood so my speech must have made an impact.

“What say you, William?” I ask, addressing Paulet.

“I agree,” he replies, hastily emptying his spoonful of meat back to the plate to answer. “You would need at least 10,000 men, though.”

“Possibly more,” Howard chips in. “Quite a lot more, I’m thinking.”

“It’s up to you, Howard,” Gardiner tells him, “to secure the numbers. Look to it heartily.”

“Yes,” Paulet concurs, “I do agree.”

“Well, don’t delay, My Lord,” I urge anxiously.

The people are with me, Howard tells me, and always have been. “Remember last year?” he asks.

“How could I forget?” I wonder. As the meal continues, my mind is in turmoil.

Sometimes I wonder why I have been so troubled and punished in my life. It should have been so straightforward and uncomplicated. The only daughter of the popular and just King Henry VIII and Queen Catherine of Aragon, we were happily united in all wise happenings for many years until my father, in his wisdom, concluded that his marriage was illegal and set out to have it annulled. Whatever possessed him to desert my mother and deny the authority of the Holy Roman Church, I shall never know. When I made it clear that I could never accept another religion and my allegiance, like my mother’s, would always be to Rome, I knew the full force of his dissatisfaction with me. What happened after that, appointing himself as head of the English church and taking another wife, I cannot bear even to think about.

“The attempt by your half-brother, Edward VI, to alter the line of succession and put your cousin Lady Jane Grey on the throne was always doomed to failure,” Howard is musing. “Look how the people rallied around you then and aided the overthrow of the usurper.”

“Yes, well, that young woman has been a thorn in my side these last six months or more,” I say bitterly. “I still don’t know what to do with her but I’ve resisted all the advice by my ministers to have her executed.”

“She is dangerous,” Howard suggests tentatively, “and fully committed to the new English church.”

“More dangerous than she looks, I grant you,” Gardiner adds, looking at Howard.

“She will be dealt with,” I advise acidly. “And we are not inclined to continue with this conversation.”

“No, I spoke out of turn. My apologies,” Howard hastily replies. Gardiner nods to indicate agreement.

Sweetmeats are brought in for our consideration; marzipan, fruits and jelly in an imaginative mould. I allow a servant to serve me an exceedingly small portion as I really wish only to take a little sweetmeat to cleanse my palate. Howard takes a plateful of sweetmeats, attacks them greedily and asks me if I will be leaving London during the next week as he recruits his volunteers for the fight with Wyatt’s villains.

“As I have made quite clear to you and others,” I insist, “I intend to stay right here. Most likely at Westminster Palace.”

“We thought, for your safety,” he begins nervously, “you would be much safer in the country, Majesty.”

“If I am not in London,” I respond irritably, “the rebels could attack government and attempt to overthrow me. No, I stay right here.”

“Windsor would be a safe haven,” Gardiner opines. “I commend it to you.”

“Not even Windsor, Your Majesty?” Paulet enquires.

“Not Windsor, not even 10 paces from Westminster. I know what I am doing and there will be no further comment on our decision.”

Howard nods his understanding to me; Gardiner and Paulet follow suit and resume their attack on the sweetmeats. I take a drink of wine from my goblet and reflect that sooner or later, before I am done, these officials and others will realise that the words and decisions of a queen have equal import with those of a king.

QUEEN MARY’S DIARY, WESTMINSTER PALACE, EARLY FEBRUARY 1554

Late afternoon on a grey day. Some small brightness licks at the lattices of the window and filters light into the chamber. It soon fades. I dislike winter days and especially as the light dims early and plunges us into night and darkness. The candles can be lit early on and usually are at my discretion, but a gloom still pervades the chamber at this time of year. The deep-brown panelling around the room seems to lose its sheen as night starts to fall. Even the colourful tapestry on the far wall appears pale and lifeless at this time of day.

I dismissed all my ladies-in-waiting a short while ago as I felt the need to be solitary and my Lady Margaret Douglas was beginning to irritate me with her tiresome anecdotes about past queens that she had heard from her many admirers. After sitting here for a while in the ever-encroaching gloom, however, I am feeling the need of at least one companion. I send for more candles and have them lit, deciding that artificial light is preferable to no light at all. I send next for Jane Dormer for, if I am to have one companion who will not irritate and darken my mood, it is she. Jane is of a bright and cheerful disposition almost always and rarely fails to brighten my mood. She is in no wise a handsome creature, but her soft features and ready smile are good enough for me; I tire very quickly of pretty women who are always preening themselves. Jane too, is small in stature, has copper-coloured hair, clear eyes and we are not unlike physically and in deportment generally. Like me, she is very short, has red hair and plain, wan skin but bright blue eyes. Physically, too, it seems, we have much in common.

She enters the chamber with a warm, bright expression on her face that cheers me immediately. I send for sweet French wine and raise my goblet with Jane. Sweet, with a hint of bitterness and as refreshing as could be desired, it perks me up immediately. Jane thinks that I look quite pleased about something and tells me so.

“You know, I was just reflecting on my speech at the Guildhall,” I confess. “My Lord Howard was gracious enough to call it magnificent.”

Jane raises an eyebrow slowly.

“What, you think I exaggerate or did not deserve the compliment?”

Jane utters a short, tinkling laugh. “I’m sure you deserved every word, although we should perhaps bear in mind that if you said black was white Howard would agree with you.”

“He wouldn’t,” I protest, unable to suppress a smile. “Anyway, you may scoff but it had the desired effect. Who could have dreamed the man would recruit 20,000 men to the militia in less than 24 hours?”

Jane agrees immediately on that point and expresses wonder that Wyatt and his rebels were crushed so swiftly and convincingly so soon after he had been successful early on in his disastrous campaign. She finds it impressive that Wyatt was lured in towards the City of London and then had the gates at Ludgate closed against him. On the other hand, she whispers satirically, it would be difficult for the finest warriors in the world to resist 20,000 armed and bloodthirsty soldiers coming towards them.

“Not all 20,000 at once,” I say, keeping a straight face and a bland expression.

“No, not that,” agrees a laughing Jane.

At any rate, it is done now and over and I can continue with my policy of restoring the authority of the Holy Roman Church in our land, safe again from those who would overthrow me, doubtless take my life and put my half-sister Elizabeth on the throne of England. It will be a long and painful process and may not even be achieved in my lifetime, but I will never rest from my attempts to complete it. There is much to do also in building up our navy to resist all attempts by those who would invade our shores and colonise us.

“When is his trial?” Jane asks.

“In a few days’ time, I am informed.”

“So soon?”

“The sooner the better. He can have no defence of his infamous behaviour. We will have his head on a spike before March is out.”

“Indeed.”

As soon as Wyatt is locked securely in the Tower, my trusted officials will interrogate him vigorously to ascertain what part Elizabeth played in this uprising. If the plan were to overthrow us and put her on the throne, I cannot believe that she was not a willing conspirator with them or, at the very least, knew of the plan and heartily approved it. He may not wish to implicate her or admit her involvement, but my interrogators are advised by me to be very, very persuasive. The truth will come out, of that I am sure. As it is a concern and worry to me, I mention my fears to Jane.

“She wouldn’t dare openly ally herself with Wyatt, surely?”

“How can I tell, Jane?” I enquire sombrely. “Members of my own family have hurt and attempted to break me as much as my worst enemies. My father, my half-brother, Lady Jane Grey and my half-sister, Elizabeth.”

Jane’s expression conveys to me that she is shocked and sympathizes with my predicament. She is a goodly friend and, I think, of all my ladies, the one I trust the most as loyal and true. She is one of few intimates to whom I have opened my heart in discussion; she knows the pain I endured when my father annulled his marriage and sent my faithful, God-fearing mother away into isolation. I never saw her again after that and I suffered grievously as a result. Worse was to come when my father, with his new wife, that Boleyn woman, had a daughter and I was assigned to wait upon her as a servant. After that, how could I ever have a normal bond with Elizabeth? Only Jane knows the full details of these transgressions against me as I had to confide in one good friend or I fear I should have gone mad.

“I can’t believe Elizabeth would be so foolhardy,” Jane muses quietly but I see from her expression that she is as doubtful as I.

“It is not just her,” I continue irritably. “Jane Grey has languished in the tower these past six months and now that her father and brother took part in Wyatt’s rebellion and traitorous upsurge, I have little choice but to have her executed. As she is my cousin, I resisted all attempts by my councillors to have her sent to the block, but I fear I can no longer do so. She is a symbol for the English church that Wyatt and his motley crew wanted to perpetuate, and she must, I regret, go to her death.”

“If that is what you must do, Mary, you will do it,” Jane says. “You are much stronger than your enemies have ever realised.”

I smile. She is right, of course. Have I not resisted an attempt by my half-brother to have me eliminated from the line of succession to claim the throne that is rightfully mine? Have I not resisted and crushed an attempt to overthrow my government, have me killed and put my half-sister on the throne? And have I not resisted the strong advice and attempted persuasion of my councillors to abandon my plan to marry Price Philip of Spain and wed an English noble?

I remind Jane of these achievements and she nods in agreement. “So what of young Philip?” she asks.

“He is tall, handsome,” I tell her cheerily, “and he will make a wonderful husband.”

“Where and when did you first meet?” she asks, grinning at me. “Tell me all.”

“We have never met,” I admit, quietly. “Yet.”

“Never met?” she says incredulously. “And never spoken?”

“Well, no, he speaks extraordinarily little English, I am informed.”

Jane laughs and shakes her head vigorously. She says I never fail to surprise and sometimes amaze her, but she knows, well enough, that I must have a plan and, knowing me, it is one that will work. She is sincere, too; I can see that in her face and the way she speaks. So many of my ladies of the court just want to please me and flatter me and I see through them all. They are tiresome. Jane is an exception.

“But how on earth will you communicate?” she wants to know.

“Come with me,” I say, rising and signalling to a servant to open the door, “and you shall see.”

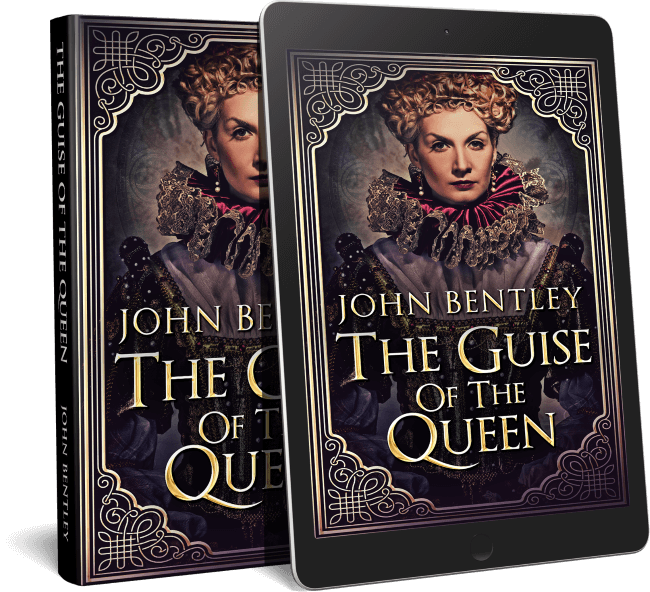

We walk into the corridor and move along until we reach the chamber where I keep my most prized possessions. On the wall that receives the most lighting from the window lattices hangs a magnificent portrait. I turn to Jane and invite her to take a good look.

“So this is Prince Philip?”

“It was sent to me from another Mary, in Europe,” I murmur softly. “They say it should be returned later.”

“And will you return it?”

“Never.”

Jane lets out a high pitched, tinkling laugh. She adds that it is, indeed, a striking portrait.

“Isn’t it? Painted by Titian and who better in Christendom to produce a more faithful likeness?”

“Impressive,” Jane breathes quietly, nodding as she looks at the portrait.

“Is he not the boldest, the most handsome man you ever set eyes upon?” I ask her. “I often come in here on a bright morning when the light is best and gaze at the portrait for ages.”

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.