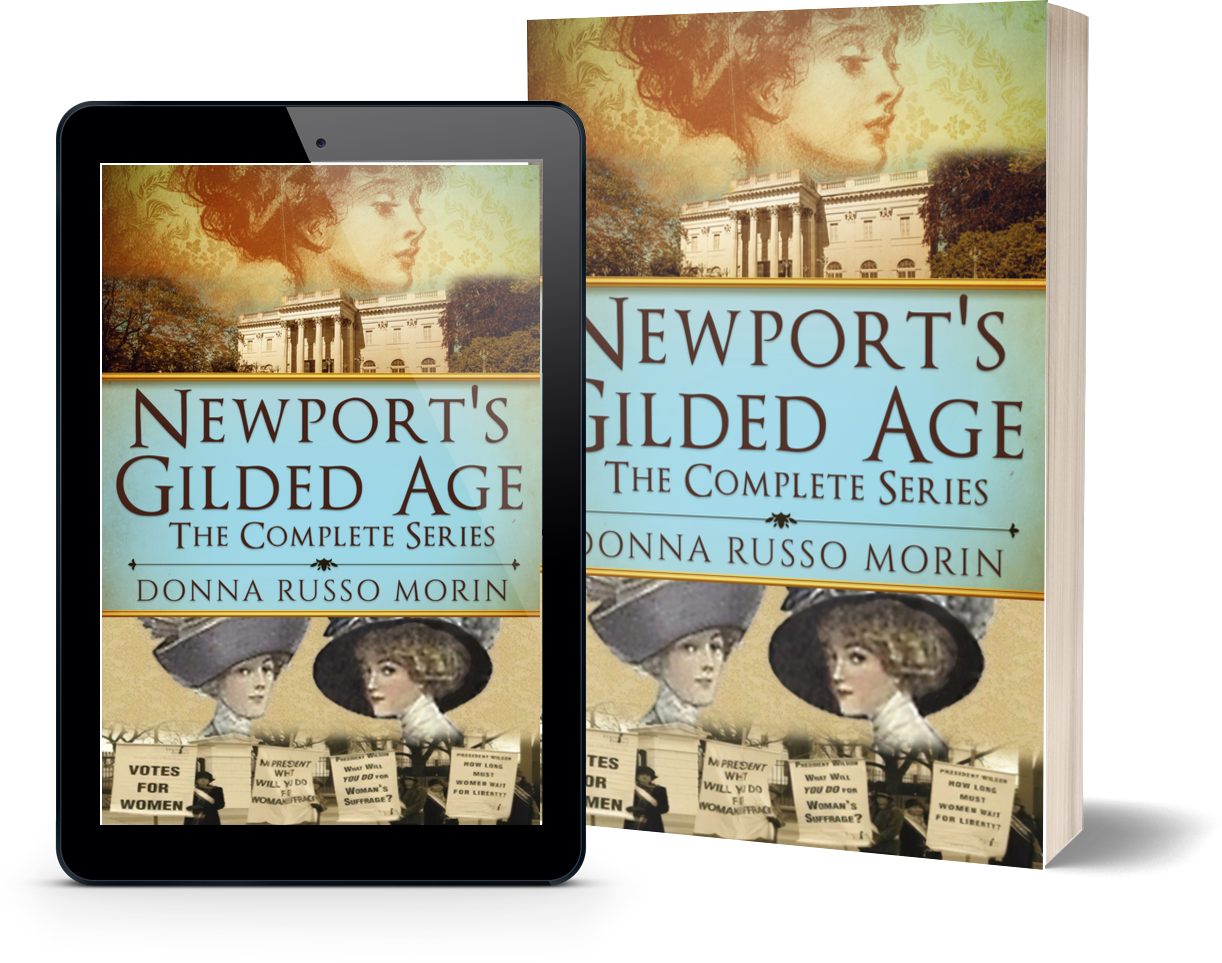

Newport's Gilded Age: The Complete Series

Book summary

Delve into the elegance and tumult of Newport's Gilded Age with Donna Russo Morin's captivating collection. Set against the lavish backdrop of Rhode Island's elite, two women, Pearl and Ginevra, traverse paths of friendship, ambition, and rebellion. From the confines of societal expectations to the forefront of the suffrage movement, their journeys embody the struggles and dreams of women of their time. As they navigate personal challenges and historic events, from the sinking of the Titanic to World War 1, their intertwined stories highlight the resilience of the human spirit and the pursuit of identity amidst a changing world. This collection offers a sweeping tale of friendship, empowerment, and the quest for self-discovery during a defining era in American history.

Excerpt from Newport's Gilded Age: The Complete Series

The man called Birch led us through the marble hall. I walked on tiptoes. I walked as I once had through a grand cathedral back in Italy.

He hurried us along. I had only seconds to glimpse a dining room, one so large it could have served as a great hall in a castle from long ago. It glittered; gold sparkled everywhere. Across from it, an alcove, each end flanked by glass and gold cabinets. On display were more treasures of silver and gold, china and porcelain. I slowed; if I could, I would have run.

The man hurried us along.

We passed through two dark, carved doors; we passed into another world. Inside these doors, we entered a small landing.

“This is a ladies' powder room,” Mr. Birch finally decided to speak to us. “The Beeches has some of the most modern plumbing in all of Newport.” He turned hard eyes on me. “Family and guests only.”

I returned his look. Nothing more.

The snobby man spoke with such pride; you would think this enormous place belonged to him. I suppose in a way he thought it did.

Everything about Birch was stiff, his perfectly pressed cut-away, pristine white shirt, large black puff tie with its big, fancy knot bobbing as he spoke, but especially the stiff tone of his voice. Did he speak to everyone with such cold flatness or did such a chill frost only my father and me? Time would tell.

My father nudged my arm and gave me 'the look.' I translated.

Such looks came constantly during our journey to America. I saw more of them than I did the passing ocean.

Mr. Worthington had paid our fare, thirty dollars each… thirty dollars to travel in the bowels of one of the great steamships crossing the ocean faster than the wind. It was a week living in hell.

Not allowed on deck, I had begun to dream of fresh air before the journey ended. They fed us little else but soup or stew, we slept in huddled masses on the floor in our clothes beside our luggage and had only salt water to wash ourselves.

Few of the others understood the sharply delivered instructions of the ship's crew given only in English. I was one of the few.

My role as translator had started then, and though I tried to teach Papa the language through the long empty hours on the ship, he had learned to say only a few words; he understood even less. Instead, he would give me 'the look' and I would translate as best I could.

The ship docked in New York. We rose up from our burial place and saw the sky, breathing deep. The sight of the giant lady and her torch overwhelmed us. We had heard of her, her welcoming. The people who worked at her feet were not so kind. I feared, despised, and pitied them. Their jobs were difficult; they could not show us too much kindness. To them, we were no different from the colored, what Italians called mulignane. The nastiness of it became my reality. They stripped away our humanity; we could have been heads of lettuce. Yet they were just doing their work.

They tagged us like cattle, put us in rooms to stand, waiting. We stood in lines for hours, herded through, telling our names over and over.

So many lost their real names. If they couldn't write, those who registered us went by sound alone, mangling many, wrong names these newcomers would carry for the rest of their lives. Worse were the ones they sent back. They had endured for nothing.

Then the inspections…our clothes, our hair, our mouths, our bodies. Endless invasions making us feel less than human. The constant questions, the same again and again. Thorough and hurried at the same time. They hurried us so fast, often I didn't have time to understand myself. They hurried us, as the butler did now, as if they couldn't wait to get us to a place where they could not see us.

Birch pointed to his left.

“This pantry here serves both the breakfast room just behind it and the dining room. A marvelous convenience for the family.”

He said mahvelous as if he were one of them.

He opened another door, plain wood and frosted glass. Into another foyer, a simple if bright one of windows and white tile. The floor, the walls, the ceiling, all of small white squares of tile. Then to the staircase.

It rose and fell away from us. I looked up and down; I could see the white grillwork and polished wood banister spiral away in perfect symmetry. I stood in the middle, moving neither up nor down. It was a landing named nowhere.

“This is the servants' staircase. It is the only staircase you shall ever use.”

Birch stopped and turned to us. “Ever.”

My father needed no translation to understand.

“They may use it from time to time.” He said “they” as if the word referred to a king or a queen. “But rarely. Downstairs, if you please,” he instructed.

I had known we traveled to a rich man's house, but I never imagined a place like this. I became aware of our ragged appearance, clothes old and worn before the hard journey, now so very much worse, our ragged suitcases holding only more ragged clothes. The coarse wool scratched me for the first time in my life. My foot shrunk away from the top step; I could not see where they led.

Before he closed the door to the marble hallway—though I didn't know then it must never be called a hallway—I looked back.

The girl still stood at her place by the pillars; she could have been a sculpture at its feet. Her clothing was so fine. Her dress was short, hem falling between knees and ankles; it puffed all around her from something that lay underneath. It seemed to hover about her, fabric as fine as angel's wings.

Something nameless, a creature I had never met, was born in me that was to live within, eating away, for many years.

She stared at us still, but it wasn't a mean stare. Curious, yes, and something else, I thought. Perhaps that something else was just my own hope.

“Wait right here.” Birch instructed me, pointing to a distinct spot at the bottom of the stairs in a large foyer of the same white tile. “Right…here.” He pointed again. I did not know which I was more compelled to do, curtsey to him or slap him.

He took my father by the arm and led him through another frosted door and then another, their footsteps growing ever fainter, their silhouettes fuzzy as if they walked out of this world to another. With each step they took, the churning in my gullet twisted tighter. I found myself standing alone amid people in constant motion. My feet once more pestered me to run.

Most were women, some middle-aged, most young. Their features as alike as their uniforms: fair-haired, light-skinned, blonde or soft brown hair, most with blue eyes like pieces of glass with pointed edges.

Praesent id libero id metus varius consectetur ac eget diam. Nulla felis nunc, consequat laoreet lacus id.